Ностальгия по-голливудски: костюмы, вдохновленные историей кино

Материал подготовлен автором на основе научной статьи «Ностальгия по-голливудски: костюмы в современных фильмах об истории американского кино» (Nostalgia, Hollywood Style: Costumes in Contemporary Films about American Cinema History), опубликованной на английском языке в журнале «Коммуникации. Медиа. Дизайн» факультета креативных индустрий НИУ ВШЭ.

Полная версия статьи доступна по ссылке.

Contemporary art and mass culture undeniably favour the phenomenon of nostalgia. The tendency for retrospection, as well as representation of the past and its images, becomes quite a distinctive feature of contemporary advertising business, design, fashion industry, cinema and television. Such attention to the process of creating an idealised image of the past and its aesthetics may be indicative of the conflicting trends in the contemporary culture. On the one hand, nostalgia can be regarded as a regressive phenomenon, which symbolises the thematic and aesthetic crisis of postmodernism. On the other hand, the reassessment of the past and the actualisation of its images in terms of the contemporary cultural context, certainly offer a way to overcome the sense of fear and frustration for the present.

This tendency for nostalgia has been evident in the film industry probably since the fall of the classic Hollywood era in the late 1960s. The specific term nostalgia film appeared for the first time as a new concept in film studies of the 1970s. The term was later rediscovered and popularised by Fredric Jameson, who applied it to a wider cultural context of postmodernism.

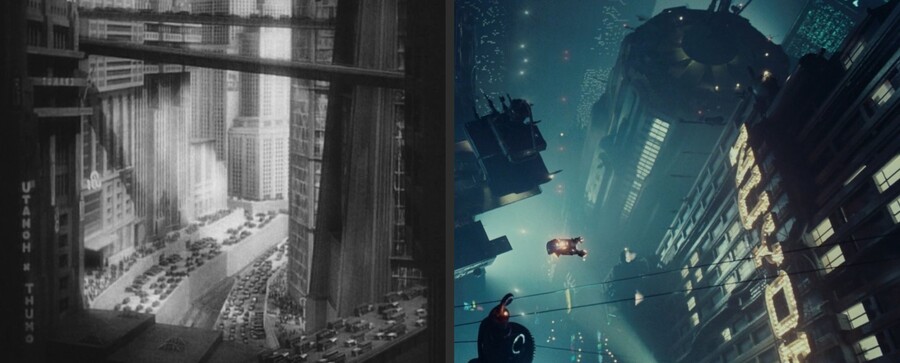

Left: Hedy Lamarr in Come Live with Me (1941, dir. Clarence Brown).

Right: Sean Young in Blade Runner (1982, dir. Ridley Scott).

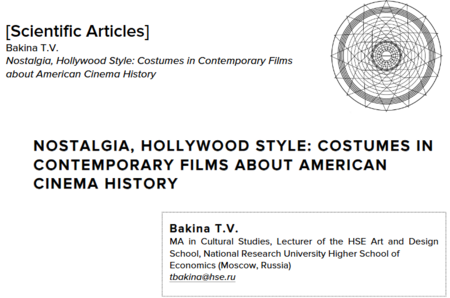

Nostalgia films differ from the historical film genre. Here the past is addressed on sensual and emotional levels, unlike the literal replication of the past in historical movies. Moreover, for nostalgia films it is sometimes not even necessary to replicate the past on screen at all. These films can be set in the present or even in the future, while remaining as nostalgic movies. For instance, while set in the future, Blade Runner (1982, dir. Ridley Scott) provokes nostalgic longing for the film noir style of the 1940s, futuristic art deco architecture inspired by Metropolis (1927, dir. Fritz Lang) and sci-fi films of the 1950s. The object of nostalgia here is not the past itself, but the mass culture of the past.

Screenshots from Metropolis (1927, dir. Fritz Lang)

and Blade Runner (1982, dir. Ridley Scott)

Nostalgic experience in such films can be provoked by means of stylisation, i.e. the reduction of cinematic language and its expressive possibilities to some archaic forms (like silent or monochrome films). Another way to visually stylise the nostalgia film is to fill the screen with material artefacts of the past, which are representative of the era they belong to, and thus can be recognised by the film audience as such.

These artefacts usually fall into categories of design and material culture: elements of interior design and old furniture, technical devices that are no longer produced, and last but not least — clothing and accessories.

Film costumes are indeed powerful instruments for reconstructing the past on screen. Being a part of characters’ identities, costumes present the visual information about the historical era and the culture they belong to. Clothing of the past is easily recognised by the audience as they mark the period of history that the film is set in, even when other visual objects on screen fail to do so. Set design, locations and material objects are no less important, but when for some reason they are not affiliated with the era the film is set in, costumes do the job of reflecting history on screen.

Despite the importance of costumes in nostalgia films, they seldom become the focus of academic research. Neither film costume historians nor film scholars try to analyse the nostalgic functions of clothing in cinema, probably because these costumes usually fall into the category of mere historical garments reconstructed for films.

Screenshot from Midnight in Paris (2011, dir. Woody Allen). Main characters travel in time from 1920s to 1890s — this explains the stylistic differences in their clothes compared to other characters.

Indeed, most costumes in nostalgia movies are more or less accurate period costumes that usually belong to the recent past. The most obvious strategy here would be to question the authenticity (or the lack of it) of these historical costumes. It works for those nostalgia films where the nostalgic object is a particular period in history, i.e. the decades of the Twentieth century and their representation in culture. But it is rather different when the films reconstruct not the mere image of the past, but instead are being nostalgic about certain objects of mass culture of the past — films, television series, comics and graphic novels etc. Here the costumes surpass the basic function of being true to the history. When working on such films, contemporary costume designers seek the inspiration in garments that belong to the fictional world addressed in these films.

Nostalgia films of the last two decades are often reflective of cinema history and of classical Hollywood movies in particular. This in a way reminds of Niklas Luhmann’s concept of self-reference. Various films of the time serve as examples of this self-referential code in contemporary cinema.

Screenshot from Hugo (2011, dir. Martin Scorsese).

Characters relive their memories of the first screen showing of cinematograph (The Arrival of the Train to the Station).

For instance, in Hugo (2011), the director Martin Scorsese aims to construct a nostalgic image of the early ‘cinema of attractions’ era. He also presents a romanticised biography of the French film pioneer Georges Méliès and pays tribute to his works. The Artist (2011, dir. Michel Hazanavicius) is a stylistic imitation of two aesthetic modes of cinema at the time: silent films of 1920s (by giving up the sound) and classic Hollywood films of 1930s (by means of visual stylisation). Woody Allen, a director who regularly returns to the subject of nostalgia throughout his career, gives a rather sentimental account of the Hollywood film industry in its blooming years in his Café Society (2016). Finally, the resonant film of Damien Chazelle, La La Land (2016), is yet another attempt to replicate the style of classical Hollywood musical film through the prism of nostalgia. Classical Hollywood films, as well as the Hollywood film industry in 1930s and 1940s, definitely are nostalgic objects in most of these films, and the key to understanding the mechanism of nostalgia here would be to examine the films of that period with a specific focus on Hollywood costume design.

Hollywood Fashions and Screen Style of 1930s to 1950s

Systematic appeal to the mythology of the Golden Age of Hollywood is not coincidental. This particular period of American cinema history is considered the most flourishing and prolific time for the industry. Hollywood films of 1930s to 1950s epitomised the results of a well-designed, standardised mode of film production. Classic Hollywood style is effortlessly recognised by the audience thanks to a combination of distinctive genre system, continuity editing, linear narrative and invisible style that leads to the cinematic visual realism. Another aspect of the Classical Hollywood style is the dominance of the Motion Picture Production Code, an ethical system of moral guidelines that was applied to practically all films that were produced during that era.

Left to Right: Screenshots from Top Hat (1935, dir. Mark Sandrich), Blonde Venus (1932, dir. Josef von Sternberg), Casablanca (1942, dir. Michael Curtiz) and Sabrina (1955, dir. Billy Wilder).

The Hollywood film industry heavily relied on the benefits of the star system. Constructing the glamorous image of actors and actresses of the era was an important part of film marketing. Stars were made by transforming ordinary people to glamorous idols with near perfect faces, adorned in fashionable clothes. Their biographies were made up, their photographs were heavily retouched, their screen images were lit by magnificent lighting. Classic Hollywood stars had an almost magnetic appeal to the audience.

Covers of Modern Screen and Photoplay movie magazines

Costumes in classic Hollywood cinema were no ordinary clothes. They functioned as a certain visual code for communication with the audience. Costume is the most important part of the character’s screen image that is perceived by the viewers at a non-verbal level. Before actors say their first lines, costumes engage in a communication with film viewers, informing the audience about characters’ background, sometimes even finishing their psychological portraits. But there’s more to it when examining the functions of Hollywood costumes of the 1930s and 1940s. These costumes were glamorous and sophisticated enough to become marketing tools that influenced the consumer behaviour of the audience. Moreover, they were the source of information for fashion trends and luxury.

Left: Sparkling Nights, fashion in film article in Photoplay magazine, October 1935.

Right: Now in Smartest Stores: Hollywood Fashions! , fashion in film article in Photoplay magazine, January 1932.

The practice of designing costumes for the silver screen in the 1930s to 1950s was handled with full attention. Each major film studio in Hollywood employed a costume designer on a full-time basis. Expensive materials and luxurious fabrics were never something to save on, even during the Great Depression times. The décor was exaggerated to the extremes: gowns sparkled with sequins, dressing gowns were trimmed with huge feathers and layers of chiffon or silk and contributed to the overall impression of luxury. These costumes were above all fashion trends, and influenced new styles and fashions at the same time. They presented an alternative to the concept of ‘Parisian chic’, but in fact, they were as inaccessible as the French couture clothing. While fashions from Paris cost much more than most people could afford, the fashions of Hollywood screen were simply too extravagant for everyday life. This, however, has not diminished the influence that Hollywood costumes had over the tastes of the audience.

Grace Kelly in To Catch a Thief (1955)

Barbara Stanwyck in Ball of Fire (1941)

Ginger Rogers in Lady in the Dark (1944)

Lauren Bacall in To Have and Have Not (1944)

In the first half of the 20th Century, the fashion industry was yet to discover the potential of filming fashion and using this as an effective advertising method. Meanwhile, feature films made in Hollywood were influencing fashion trends and setting new styles. Hollywood cinema has always been an art for the masses, while the couture fashion industry was famous for its exclusivity and general inaccessibility. Along with the classic channels of distributing current trends in fashion — printed magazines and advertising — films presented the fashionable costumes in movement and thus informed the mass audiences of what was considered chic at the time. The Hollywood screen was functioning as a catwalk where beautiful actresses slowly paraded through luxurious sets, representing the idea of a high life, this Hollywood myth of well-being that became an important cultural concept at the time.

Left: Fashion Forecast for Autumn, article by Travis Banton in Photoplay magazine, September 1935.

Right: 1935 Interpretations of Classic Modes, fashion in film article in Photoplay, October 1935.

Though seemingly unreachable, this idea of a high life soon invaded the consumer society on several levels. The interest that the audience showed to the Hollywood film costumes of the 1930s resulted in the emergence of new commercial models. They were aimed to both advertise film fashions and reproduce them as new fashionable clothing lines inspired by the creativity of Hollywood costume designers. A notable example of this new business mode was an enterprise created by Bernard Waldman. His Modern Merchandising Bureau launched the chain of Cinema Fashions boutiques, where an assortment of clothes consisted exclusively of Hollywood film costumes. Evening gowns and day suits were simplified and adapted to the needs of everyday life.

Scenes from promotional film «Hollywood — Style Center of the World» (1940, dir. Oliver Garver, by Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer)

The business operated as following. Costume sketches for upcoming motion pictures reached Waldman directly from Hollywood studios long before these films were released in movie theatres. The Bureau’s staff then estimated these sketches — only those models that had the potential to be sold went into production. Selected models were then simplified to be mass produced. The most extravagant costumes thus never made it to the stores because of their impracticality. When films that inspired these clothes were finally released, the boutiques all over the country were already filled with costume replicas with advertising materials attached. These materials included photographs and film production stills with the costume depicted on the actress who wore the garment on screen. Naturally, it went with references to the studio that produced the film, as well as its principal cast and crew. This commodification of film costumes was extremely profitable for both Waldman’s Bureau and Hollywood studios that received extra publicity. The cost of these replicas was much high than average — thus, it contributed to the aura of exclusiveness and seeming inaccessibility of the Hollywood ideal.

Scenes from promotional film «Hollywood — Style Center of the World» (1940, dir. Oliver Garver, by Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer)

Commodification affected the cosmetics industry as well. Since 1920s, the products of Max Factor brand became available to general customers. The brand’s reputation preceded itself. Max Factor was famous for creating innovative cosmetic goods exclusively for Hollywood actors and actresses that could transform any face to an iconic beauty. Advertising materials and magazine articles featuring the latest trends in make-up reassured its audience that everyone can become a star. Mastering the art of applying the make-up in Hollywood style was said to be the only thing needed for it.

Nostalgia for the Classic Hollywood Style in Contemporary American Cinema

The images and styles of Classic Hollywood cinema are frequently addressed in contemporary nostalgia films. It is probably most common for revisionist films that replicate popular film genres of the past on a level of visual stylisation.

Sometimes such films appeal to nostalgic aesthetics on a more formal level. They attempt to mimic original motion pictures by deliberately limiting the expressive possibilities of modern cinema language and turning to archaic modes of production.

But mostly it is enough to show the fictional world on screen in the same way it was shown in the films of the past, to achieve the nostalgic effect. Whether this world would be presented as nostalgically idealised or not depends on the generic nature of original films, for the object of nostalgia here is not the historical era depicted on screen, but the films of this era themselves, as a distinctive feature of the mass culture of that period.

Opening scene from La La Land (2016, dir. Damien Chazelle), showing the transition from the 4:3 aspect ratio, that was a Classical Hollywood standard, to a widescreen CinemaScope format of 1950s.

For instance, the reconstruction of film genres and styles of the past takes place in King Kong (2005, dir. Peter Jackson) and Far From Heaven (2002, dir. Todd Haynes). While King Kong happens to be an accurate remake of the 1933 original motion picture, Far From Heaven is more of an homage to the Hollywood melodrama films of 1950s. Its visual style resembles that of Douglas Sirk classic films, focusing primarily on replicating vivid colours of the Technicolor system, a process that was used to colorize Hollywood films from the 1930s to 1960s.

Left: Jane Wyman in All that Heaven Allows (1955, dir. Douglas Sirk)

Right: Julianne Moore in Far from Heaven (2002, dir. Todd Haynes)

Stories about the past of the American film industry itself, as well as biographical films about people who were affiliated with Hollywood at the time, deserve specific attention and deeper research. Beside the replication of classical film aesthetics, these movies examine the nostalgic image of Hollywood as a star factory, the epitome of movie magic and glamorous lifestyle. Nonetheless, in these films the nostalgic effect often goes together with the critique on the industry and the examinations of its darker sides. Certain aspects of Hollywood lifestyle are being romanticised, while other aspects connected with the industry are depicted in the light of irony or straightforward criticism.

Scene from Hollywood (TV Miniseries, 2020, created by R. Murphy and I. Brennan, Netflix).

Fictional photoshoot of Hollywood rising stars by real-life photographer George Hurrell, played by A. Bristow

As noted previously, film costumes constitute the particular part of aesthetics of the past that are easily recognised by the audience as such. It is especially relevant to the nostalgic depiction of the old Hollywood style. The methods used to reproduce this aesthetic model vary greatly as they depend on different film contexts. Therefore, analysing these methods would contribute to the research field that covers various functions of film costumes, but seldom focuses on the nostalgic effect they might produce.

Costumes that provoke nostalgia for the past are usually related to this past. The connection, however, is not as evident for costumes in films set in the present time or future. Addition of retro style elements to current fashion trends is a much more complicated task.

The examining of several specific cases would allow us to trace differences in both approaches.

Films with storylines that directly or indirectly address the Golden Age of Hollywood are usually filled with glamorous images of classic stars, imitations of key elements of films that were made during that era and some visual markers of the time that provoke the impression of being historically accurate. In The Artist the nostalgic effect is achieved by representing two obsolete modes of film production — silent films of the 1920s and musical films of the 1930s. The main female character of the film, Peppy Miller (Berenice Bejo), goes all the way from being a movie fan who accidentally got photographed with a Hollywood star, to an aspiring supporting actress and, finally — to becoming a movie icon herself in the early days of sound film.

Her costumes reflect her changing status. She is first seen in simple day suits in the style of the late 1920s that don’t make her stand out. Her simple clothing in the beginning of the film emphasises her status as an ordinary girl who dreams of becoming a film star but which is unlikely to ever come true, unless for a lucky coincidence. Her image contrasts with that of her movie idol, George Valentin (Jean Dujardin), who is always seen in shining tuxedos and smart tailored suits. As their careers shift over the course of the film, Peppy’s wardrobe gets filled with elegant dresses and sequined evening gowns. These dashing looks also reflect the changing fashion trends of 1929 and 1930. From loose dresses with a dropped waist and shortened hemline, fashions quickly changed to longer and tighter feminine silhouettes and elegant bias cut gowns that epitomised the 1930s.

With her career on the rise, Peppy acquires fur coats and chic veiled hats that correspond with her changing status. Her new position as a starlet calls for such classy and sophisticated styles because they match the expectations of how the Hollywood star should look. The emphasis on exquisite accessories in Peppy’s looks is also determined by the fact that such decorative materials and fabrics as fur, ostrich feathers, sequins and translucent veils were especially useful for creating the Hollywood stars’ glamorous images in the 1930s. For instance, veiled hats, fur trims and feathers helped Travis Banton, the Paramount studio’s costume designer in the 1930s, in creating a star image for Marlene Dietrich in her first Hollywood movies.

Библиографическая ссылка: Бакина Т. В. Ностальгия по-голливудски: костюмы в современных фильмах об истории американского кино // Коммуникации. Медиа. Дизайн. 2019. Т. 4. № 2. С. 129-141. For citations: Bakina T. V. Nostalgia, Hollywood Style: Costumes in Contemporary Films about American Cinema History // Communications. Media. Design. 2019. Vol. 4, No. 2.

Электронное ежеквартальное рецензируемое научное издание «Коммуникации. Медиа. Дизайн» издается при Факультете креативных индустрий НИУ-ВШЭ с 2016 года. Зарегистрирован в Российском индексе научного цитирования (РИНЦ), а также входит в «белый список» Наукометрического центра НИУ ВШЭ.